Is Natural Gas Truly Sustainable? Expert Analysis

Natural gas has long been positioned as a transitional energy source—cleaner than coal, more abundant than oil, and seemingly a bridge toward a renewable energy future. Yet the question of whether natural gas is truly sustainable remains hotly debated among environmental scientists, energy experts, and climate advocates. While natural gas does produce fewer carbon emissions than fossil fuels like coal during combustion, the complete lifecycle assessment reveals a far more complex sustainability picture that demands rigorous scrutiny.

This comprehensive analysis examines the multifaceted dimensions of natural gas sustainability, from extraction methods and methane leakage to infrastructure investment and climate impact. Understanding the true sustainability of natural gas requires looking beyond marketing narratives and examining hard scientific evidence, industry practices, and long-term environmental consequences. Whether natural gas deserves its reputation as a sustainable bridge fuel or whether it represents a dangerous distraction from genuine renewable energy transition depends heavily on how we measure sustainability and what timeline we consider.

What Defines Sustainability in Energy

Sustainability in energy encompasses multiple dimensions that extend far beyond simple carbon accounting. A truly sustainable energy source must meet several criteria: minimal environmental impact throughout its entire lifecycle, social equity and community benefit, economic viability without perpetual subsidies, resource availability for future generations, and alignment with climate goals. When we apply these rigorous standards to natural gas, the assessment becomes considerably more nuanced than industry marketing suggests.

The Environmental Protection Agency provides comprehensive data on energy source emissions, helping contextualize natural gas within the broader energy landscape. True sustainability requires examining not just direct emissions from burning fuel, but also upstream emissions from extraction, processing, transportation, and infrastructure construction. Additionally, we must consider water usage, land disruption, ecosystem impacts, and the opportunity costs of investing in natural gas infrastructure instead of renewable alternatives.

Our exploration of whether natural gas is renewable reveals fundamental distinctions between renewable and sustainable energy. While natural gas is neither renewable nor infinite, some argue it can be produced and consumed sustainably if methane leakage is minimized and emissions are captured. However, this requires technological advances and regulatory frameworks that remain inconsistently implemented across the industry.

Natural Gas Extraction and Production

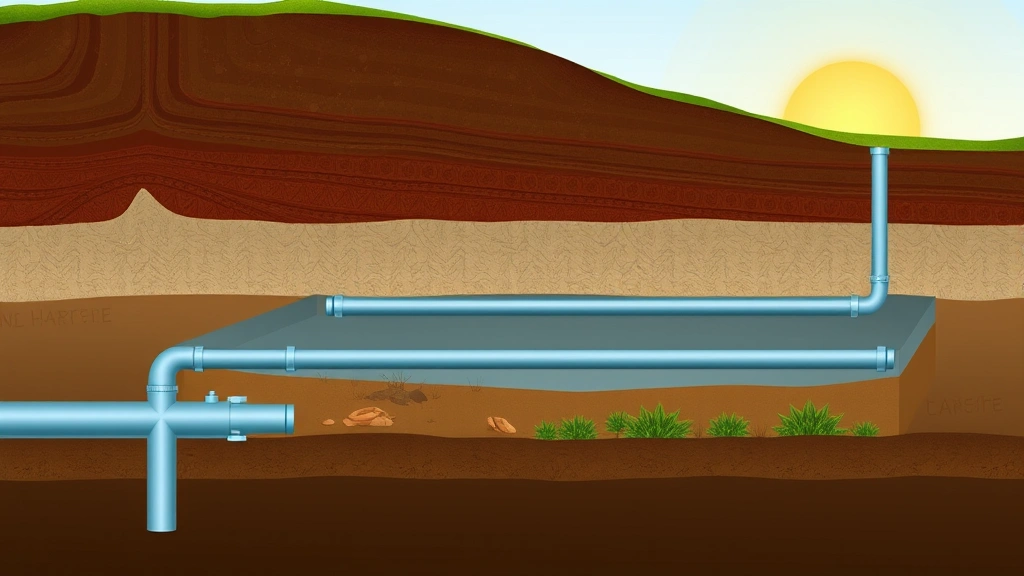

The journey of natural gas from reservoir to consumer involves numerous sustainability considerations. Conventional natural gas extraction from deep geological formations requires significant infrastructure, including drilling equipment, pipelines, and processing facilities. Each component carries environmental costs and risks. Unconventional sources like shale gas require hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which involves injecting millions of gallons of water mixed with chemicals into rock formations to release trapped gas.

Fracking operations consume enormous quantities of freshwater—typically 2-8 million gallons per well—in regions that may already face water scarcity challenges. The process generates wastewater containing radioactive elements and toxic chemicals that require careful management to prevent groundwater contamination. While the industry claims modern practices adequately protect water resources, numerous documented incidents of groundwater contamination near fracking sites raise legitimate sustainability concerns. The disposal of wastewater itself presents environmental challenges, whether through deep-well injection, surface disposal, or treatment facility processing.

Land use impacts accompany natural gas production, particularly with unconventional extraction. Shale gas operations require extensive well pad development, access roads, and associated infrastructure across landscapes. This habitat fragmentation affects wildlife migration patterns and ecosystem integrity. The cumulative landscape transformation across major shale gas regions like the Permian Basin, Marcellus Shale, and Eagle Ford Shale represents substantial environmental disruption that persists for decades.

Processing natural gas to pipeline-quality standards requires energy input, typically from burning some of the gas itself or using other fossil fuels. This parasitic energy load, while generally small, represents another efficiency loss in the overall energy chain. The chemical processing to remove impurities, water vapor, and other components generates waste streams requiring proper disposal, though modern facilities have improved waste management considerably compared to historical practices.

Methane Emissions and Climate Impact

The most critical sustainability issue surrounding natural gas centers on methane emissions. Methane, the primary component of natural gas, is a potent greenhouse gas with a global warming potential approximately 28-36 times greater than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period, or 80-86 times greater over 20 years. This distinction matters profoundly for near-term climate goals. Even small percentage leakage rates substantially undermine natural gas’s climate benefits compared to coal.

Methane escapes throughout the natural gas supply chain: during extraction and processing at wellheads, through leaks in transmission pipelines, at distribution points, during storage operations, and at end-use facilities. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates total methane emissions from natural gas systems, though independent researchers often find higher actual leakage rates than official estimates suggest. Older pipeline infrastructure particularly contributes to losses, with some systems losing 2-4% of gas through leaks—a rate that completely negates climate advantages over coal for electricity generation.

Satellite data and atmospheric measurements increasingly reveal methane hotspots over major natural gas producing regions, confirming that actual emissions exceed reported figures. Studies using independent measurement methods consistently find leakage rates higher than industry-reported numbers, suggesting systematic underestimation of methane’s true climate impact. This measurement uncertainty itself represents a sustainability concern, as policies and investment decisions rest on potentially inaccurate emission data.

The climate impact calculus for natural gas depends critically on the leakage rate threshold. If total system leakage stays below approximately 2%, natural gas provides climate benefits compared to coal. Above that threshold, natural gas becomes climatically worse than coal when methane’s superior warming potential is properly weighted. Independent research suggests many regional systems exceed this critical threshold, particularly when including upstream, distribution, and end-use losses. This reality fundamentally challenges natural gas’s sustainability narrative.

Comparing Natural Gas to Other Energy Sources

When assessed against alternative energy sources, natural gas’s sustainability profile becomes clearer through comparative analysis. Compared to coal, natural gas produces roughly half the carbon dioxide emissions during combustion, making it superior from a direct emissions perspective. However, when methane leakage is included and weighted appropriately, this advantage diminishes or disappears depending on actual leakage rates in specific systems.

Our examination of sustainable energy solutions reveals that renewable sources like wind, solar, and hydroelectric power generate electricity with minimal lifecycle emissions—typically 10-50 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour, compared to 400-1000+ grams for natural gas plants when methane is properly accounted for. Battery storage technology, while not yet perfect, continues improving in cost and efficiency, addressing intermittency concerns that historically favored natural gas as a flexible backup resource.

Nuclear power, despite political controversy, generates electricity with lifecycle emissions comparable to wind and solar—approximately 12 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour—making it substantially cleaner than natural gas. Geothermal energy, where geographically available, provides consistent renewable power with minimal environmental impact. Even biomass and biogas, when sustainably sourced from waste streams rather than dedicated energy crops, offer lower-carbon alternatives to fossil natural gas.

The comparison becomes particularly striking when considering energy efficiency improvements. Investments in building insulation, heat pump technology, and industrial efficiency improvements often provide greater emissions reductions per dollar spent than natural gas infrastructure expansion. The opportunity cost of natural gas investment—capital that could fund renewable energy, storage, and efficiency—represents a crucial sustainability consideration often overlooked in energy planning.

Infrastructure Lock-In Effects

One of the most significant sustainability challenges with natural gas involves infrastructure lock-in—the tendency for long-lived capital investments to persist far beyond their economic and environmental justification. Natural gas pipelines, storage facilities, power plants, and distribution networks represent multi-billion-dollar infrastructure built to operate for 40-60 years. Once constructed, this infrastructure creates powerful economic and political incentives to continue using natural gas regardless of technological alternatives or climate imperatives.

Utilities and energy companies have invested heavily in natural gas infrastructure, creating financial interests aligned with maintaining and expanding gas consumption. Regulatory frameworks often guarantee returns on these investments, effectively socializing the risk while privatizing profits. This creates perverse incentives: companies profit from expanding gas infrastructure even when renewable alternatives become more economical. Stranded assets—infrastructure that becomes economically obsolete before the end of its physical life—pose risks to both utilities and consumers.

The expansion of liquefied natural gas (LNG) infrastructure exemplifies lock-in concerns particularly acutely. Multi-billion-dollar LNG export facilities, regasification terminals, and specialized shipping infrastructure represent 20-30 year commitments to natural gas markets. These investments create powerful incentives to maintain global demand for natural gas, potentially undermining climate goals. Countries and regions that build LNG infrastructure become economically dependent on continued gas exports, creating political resistance to energy transitions.

Residential and commercial heating infrastructure presents another lock-in dimension. Millions of buildings use natural gas furnaces, water heaters, and cooking appliances. Replacing this infrastructure with electric heat pumps and induction cooking requires coordinated investment and consumer behavior change. However, the existence of extensive gas distribution networks makes natural gas retrofits cheaper than electrification, perpetuating dependency on fossil fuels despite superior alternatives becoming available.

Current Industry Standards and Regulations

The regulatory framework governing natural gas production and distribution significantly influences actual sustainability outcomes. The EPA’s natural gas air pollution standards establish minimum requirements, but these regulations have often lagged behind scientific understanding of methane’s climate impact. State-level regulations vary dramatically, with some jurisdictions imposing stringent methane controls while others maintain minimal requirements.

Recent regulatory developments have attempted to address methane leakage through monitoring and reporting requirements, but enforcement remains inconsistent. The EPA’s updated methane emissions standards, while representing improvement over previous rules, still permit leakage rates that many climate scientists argue are incompatible with climate goals. Industry compliance records show mixed results, with some operators achieving low leakage rates while others exceed permitted levels.

Certification programs and sustainability standards for natural gas remain controversial. Efforts to develop “renewable natural gas” or “biomethane” from waste streams represent genuine sustainability improvements, but the volumes available remain limited compared to total natural gas consumption. Distinguishing truly sustainable biomethane from conventional natural gas in integrated pipeline systems poses practical challenges. Carbon offset programs related to natural gas often face criticism for overstating actual emissions reductions.

International frameworks addressing natural gas sustainability remain underdeveloped. Unlike renewable energy, which benefits from global commitment through climate agreements, natural gas lacks comparable international sustainability standards. This creates opportunities for “regulatory arbitrage,” where companies operate to lower standards in less-regulated jurisdictions. The lack of global standards complicates efforts to ensure that natural gas, wherever produced, meets consistent sustainability criteria.

Future Prospects and Alternatives

The future sustainability of natural gas depends on technological developments, regulatory evolution, and energy market dynamics. Emerging technologies offer potential improvements: advanced leak detection using infrared imaging and satellite data could identify and repair leaks more rapidly; carbon capture and storage could theoretically eliminate CO2 emissions from natural gas combustion; hydrogen blending could reduce carbon intensity of gas supplies. However, these technologies remain expensive, partially proven, or commercially unavailable at scale.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, while theoretically capable of reducing natural gas emissions to near-zero, remains economically challenging and has achieved limited commercial deployment. The energy requirements for capturing, compressing, and storing CO2 reduce the net energy output significantly. Permanent storage verification poses challenges, and the long-term integrity of storage sites remains uncertain. Current CCS projects operate at far below the scale required to meaningfully address global natural gas emissions.

Hydrogen produced from renewable electricity represents a potential long-term alternative to fossil natural gas. Green hydrogen could theoretically replace natural gas in many applications, using existing infrastructure with modifications. However, hydrogen production, distribution, and storage technologies require substantial development and cost reduction. Current hydrogen production overwhelmingly relies on natural gas reforming, creating circular dependencies. The infrastructure for hydrogen distribution doesn’t yet exist at meaningful scale, requiring parallel investment to natural gas infrastructure.

Our analysis of advantages of electric vehicles illustrates broader transportation electrification trends that reduce natural gas demand in some sectors. Similarly, comparing gas versus electric appliances reveals the sustainability case for electrification across residential and commercial applications. Heat pump technology for space heating and water heating offers superior efficiency and lower emissions when powered by renewable electricity, reducing natural gas dependency.

The most sustainable energy future likely involves dramatically reduced natural gas consumption rather than sustained reliance on fossil or renewable natural gas. Renewable electricity expansion, energy efficiency improvements, electrification of transportation and heating, and emerging technologies like advanced batteries and green hydrogen offer pathways to deep decarbonization without requiring massive natural gas infrastructure investment. Tracking natural gas news and developments helps stakeholders understand evolving industry dynamics and policy responses to sustainability challenges.

Renewable energy deployment continues accelerating, with solar and wind achieving cost parity with natural gas in many markets and cost advantages in others. Energy storage technology improvements and cost reductions address intermittency concerns that historically justified natural gas infrastructure. The convergence of these trends suggests that natural gas’s role in sustainable energy futures will likely diminish rather than expand, regardless of improvements to natural gas production and consumption practices.

FAQ

Is natural gas considered a renewable energy source?

No, natural gas is not renewable. It’s a fossil fuel formed from ancient organic matter, with finite reserves that require millions of years to form. However, some distinguish between fossil natural gas and biomethane produced from organic waste, which can be considered renewable if sustainably sourced. The key distinction is that natural gas reserves deplete over time, whereas truly renewable energy sources like solar and wind are continuously replenished by natural processes.

How much methane leakage makes natural gas worse than coal?

Research indicates that if total system methane leakage exceeds approximately 2-3% of gas production, natural gas becomes climatically worse than coal when methane’s superior warming potential is properly weighted over relevant timeframes. Many studies suggest actual leakage rates in various systems exceed these thresholds, particularly when including upstream, distribution, and end-use losses. This critical threshold varies depending on assumptions about methane’s global warming potential and the time horizon considered.

Can natural gas infrastructure be converted to hydrogen?

Existing natural gas infrastructure can potentially be adapted to transport hydrogen, but significant modifications would be required. Hydrogen causes embrittlement in certain materials, requiring pipeline upgrades or replacement. Compression and storage requirements differ from natural gas, necessitating equipment modifications. While theoretically possible, the cost and timeline for converting existing infrastructure to hydrogen remain uncertain. New hydrogen infrastructure might prove more practical than retrofitting existing natural gas systems.

What percentage of natural gas comes from fracking?

In the United States, approximately 70% of natural gas production involves hydraulic fracturing, with the remainder from conventional wells. Globally, the percentage is lower, as many countries rely more heavily on conventional natural gas from deep geological formations. Fracking’s rapid expansion over the past 15 years transformed U.S. energy production but introduced new environmental concerns related to water usage, contamination risks, and induced seismicity.

Is biomethane truly sustainable?

Biomethane produced from organic waste streams like agricultural residues, wastewater treatment, or landfill gas can offer genuine sustainability benefits compared to fossil natural gas. However, sustainability depends on production methods, feedstock sourcing, and land use impacts. Biomethane from dedicated energy crops competes with food production and may drive deforestation, reducing sustainability advantages. Current biomethane volumes remain limited—less than 1% of total natural gas supply—constraining its role in large-scale energy transitions.

What role will natural gas play in future energy systems?

Most climate scenarios suggest natural gas consumption will decline substantially in sustainable energy futures. Natural gas may retain limited roles in specific applications where electrification proves impractical, but the dominant trends point toward renewable electricity expansion, energy efficiency, electrification, and emerging technologies like green hydrogen. Rather than natural gas serving as a long-term bridge fuel, renewable energy increasingly offers superior economics and environmental performance, accelerating the transition away from natural gas dependency.