Is Natural Gas Sustainable? Analyzing the Impact

Natural gas has long been positioned as a cleaner alternative to coal and oil, but the question of its true sustainability remains complex and contested among environmental scientists. While it produces fewer emissions than traditional fossil fuels during combustion, the complete lifecycle of natural gas extraction, processing, transportation, and use reveals significant environmental challenges that deserve closer examination. Understanding whether natural gas can genuinely be considered sustainable requires analyzing both its benefits and substantial drawbacks in our transition toward a truly clean energy future.

The global energy landscape continues to shift as nations grapple with climate commitments and the need for reliable power sources. Natural gas occupies an interesting middle ground—cleaner than coal yet problematic compared to renewable alternatives. This comprehensive analysis explores the multifaceted sustainability implications of natural gas, examining its role in greenhouse gas emissions, methane leakage, extraction methods, and how it compares to other energy solutions available today.

Understanding Natural Gas Composition and Sources

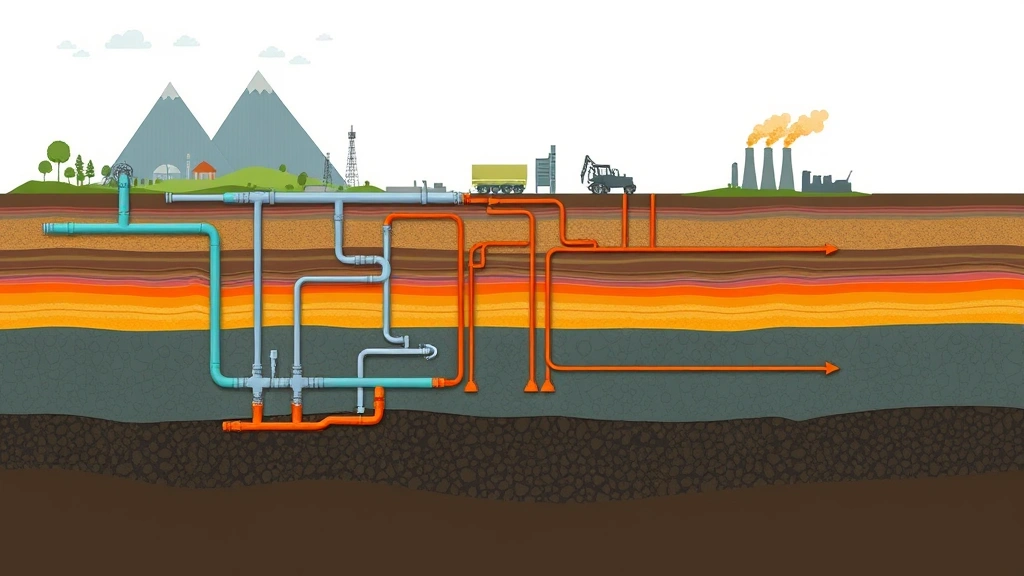

Natural gas is primarily composed of methane, a hydrocarbon that exists in gaseous form at standard temperature and pressure. This fossil fuel forms over millions of years from organic matter buried deep within the Earth’s crust, making it a non-renewable resource despite its relatively abundant supplies. The gas is extracted from underground reservoirs, often found alongside crude oil deposits, and can be accessed through conventional drilling or unconventional methods like hydraulic fracturing.

The composition of natural gas varies by source, typically containing 70-90% methane along with ethane, propane, butane, and other hydrocarbons. It also may contain impurities such as hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen, which must be removed during processing. Understanding this composition is crucial because methane itself is a potent greenhouse gas—approximately 28-34 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period, according to EPA greenhouse gas data.

Natural gas deposits are distributed globally, with major reserves in Russia, Iran, Qatar, and the United States. The accessibility of these reserves varies significantly, influencing extraction costs and environmental impact. Conventional natural gas extraction from deep wells differs substantially from shale gas extraction through hydraulic fracturing, with each method presenting distinct sustainability concerns that we must evaluate thoroughly.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Impact

When burned for electricity generation, heating, or transportation, natural gas produces significantly fewer carbon dioxide emissions than coal—approximately 50% less according to most analyses. This reduction in CO2 emissions per unit of energy is one primary reason natural gas has been promoted as a sustainable energy solution in many decarbonization strategies. However, this apparent benefit masks deeper complexities when examining the complete lifecycle of natural gas energy production.

The combustion of one unit of natural gas generates roughly 0.185 kg of CO2, compared to 0.365 kg for coal and 0.250 kg for oil. This mathematical advantage has led policymakers and energy companies to view natural gas as a transitional fuel bridge toward renewable energy adoption. Yet this perspective increasingly faces criticism from climate scientists who argue that reliance on natural gas delays the necessary shift to truly clean energy sources and locks in decades of continued fossil fuel infrastructure.

Beyond direct combustion emissions, we must consider the complete carbon footprint including extraction, processing, compression, transportation, and distribution. These upstream processes contribute additional emissions that reduce the overall climate benefit of natural gas compared to coal. According to IPCC climate research, a comprehensive lifecycle assessment reveals that natural gas’s climate advantage diminishes significantly when methane leakage is factored into calculations.

Methane Leakage: The Hidden Problem

The most critical sustainability challenge associated with natural gas is methane leakage throughout the supply chain. Methane escapes during extraction, processing, compression, transportation through pipelines, and distribution to end users. These emissions represent not only lost product but also a substantial climate impact that many sustainability analyses fail to adequately address. Studies suggest that between 1-8% of natural gas produced escapes as methane, depending on infrastructure age, maintenance standards, and extraction methods employed.

Methane’s global warming potential far exceeds that of carbon dioxide. Over a 20-year timeframe, methane is approximately 80-86 times more effective at trapping atmospheric heat than CO2. This means that even relatively small methane leakage rates can substantially negate the climate benefits of natural gas combustion compared to coal. Research from major universities and environmental organizations indicates that if methane leakage rates exceed 3-4% of production, natural gas provides no climate advantage over coal—and may actually worsen climate outcomes.

Infrastructure age plays a crucial role in methane leakage rates. Aging pipelines, compressor stations, and distribution systems in developed nations frequently leak more than modern facilities. Upgrading this infrastructure requires massive capital investment, creating a tension between economic considerations and environmental responsibility. Many utilities have deferred maintenance, prioritizing short-term profits over long-term sustainability and climate protection. The Environmental Defense Fund has conducted extensive research documenting methane leakage across American natural gas infrastructure, revealing systemic problems requiring urgent attention.

Unconventional extraction methods, particularly hydraulic fracturing or “fracking,” present additional methane leakage risks. The process of injecting high-pressure fluid into rock formations to release trapped gas creates potential pathways for methane escape. Studies examining methane emissions from shale gas operations have found leakage rates that sometimes exceed those from conventional natural gas fields, raising serious questions about the sustainability credentials of this extraction method.

Extraction and Production Methods

Natural gas extraction employs several distinct methodologies, each with different environmental implications. Conventional extraction involves drilling vertical wells into established natural gas reservoirs, a relatively mature technology with well-understood impacts. These operations require careful site management, proper well construction, and comprehensive monitoring to prevent environmental contamination. When properly executed, conventional natural gas extraction can minimize surface disturbance compared to alternative extraction methods.

Hydraulic fracturing represents a more invasive extraction approach that has dramatically increased natural gas production in recent decades. This method involves drilling wells thousands of feet deep, then injecting massive volumes of water, sand, and chemicals at extreme pressure to fracture rock formations and release trapped gas. The process generates numerous environmental concerns including groundwater contamination risks, induced seismicity, enormous freshwater consumption, and substantial chemical waste requiring treatment and disposal.

Coal bed methane extraction represents another unconventional approach, targeting methane trapped within coal seams. This method can produce methane that would otherwise escape into the atmosphere during coal mining, potentially preventing emissions. However, coal bed methane extraction often requires extensive water removal from coal seams, creating water management challenges and potential impacts on local hydrology. The sustainability benefits of this approach remain disputed among environmental scientists.

Arctic natural gas extraction presents particularly acute sustainability concerns. Developing gas reserves in Arctic regions requires extensive infrastructure in fragile ecosystems, increases climate risks by contributing to atmospheric warming that accelerates ice melt, and creates potential for catastrophic environmental damage from spills or accidents in remote regions where cleanup capacity is minimal. Many climate scientists argue that Arctic natural gas development is fundamentally incompatible with achieving climate stability.

Comparison with Renewable Energy Sources

When evaluating natural gas sustainability, direct comparison with renewable energy alternatives reveals significant shortcomings. Solar, wind, hydroelectric, and geothermal energy sources produce electricity with minimal lifecycle emissions, no fuel extraction impacts, and no methane leakage risks. Renewable energy costs have declined dramatically over the past decade, making them increasingly competitive with natural gas on economic grounds while offering superior environmental performance.

Solar photovoltaic systems generate electricity with lifecycle emissions of approximately 0.041-0.048 kg CO2 per kilowatt-hour, roughly one-quarter that of natural gas when accounting for methane leakage. Wind energy produces even lower emissions, around 0.011 kg CO2 per kilowatt-hour. These renewable alternatives avoid the ongoing extraction impacts, supply chain emissions, and climate risks inherent in natural gas systems. As battery storage technology improves, the reliability concerns that once favored natural gas become increasingly moot.

Exploring green technology innovations demonstrates that truly sustainable energy systems rely on renewable sources combined with energy efficiency improvements and storage solutions. Natural gas, by contrast, represents continued dependence on fossil fuel extraction and combustion, perpetuating environmental damage and climate risks. The economic case for natural gas increasingly depends on legacy infrastructure investments and market inertia rather than genuine sustainability advantages.

Electric vehicles and heat pumps powered by renewable electricity offer cleaner alternatives to natural gas heating and transportation applications. While natural gas vehicles produce lower emissions than gasoline-powered cars, they remain dirtier than electric vehicles charged with clean electricity. Similarly, heat pumps operating on renewable power provide superior environmental performance compared to natural gas heating systems. These alternatives demonstrate that natural gas is not a necessary component of a sustainable energy future.

Economic and Infrastructure Considerations

Natural gas infrastructure represents trillions of dollars in global investment, creating powerful economic incentives to continue relying on this fuel source. Pipelines, processing facilities, distribution networks, and power plants designed for natural gas operation comprise substantial assets that energy companies and utilities seek to protect. This economic reality, while understandable from a business perspective, conflicts with genuine sustainability imperatives and climate protection goals.

The stranded assets problem presents a fundamental challenge to natural gas sustainability narratives. As renewable energy and climate policies increasingly constrain fossil fuel use, existing natural gas infrastructure becomes economically vulnerable. Companies have responded by promoting natural gas as a “bridge fuel” toward renewables—a concept that many climate scientists now reject as incompatible with Paris Agreement targets. Building new natural gas infrastructure locks in decades of continued fossil fuel dependence, delaying the necessary transition to truly clean energy.

Understanding the natural gas versus propane comparison reveals that propane presents similar challenges. Both represent fossil fuels with extraction impacts and combustion emissions, though propane offers slightly different characteristics. For genuine sustainability, neither represents optimal solutions compared to renewable energy alternatives and electrification strategies.

Job creation arguments frequently favor natural gas development, claiming that extraction, processing, and distribution provide employment. However, renewable energy sectors increasingly demonstrate superior job creation potential relative to energy output. Solar and wind industries employ more workers per unit of energy generated than natural gas, providing economic benefits without fossil fuel dependence. Supporting workers in natural gas industries while transitioning to renewables requires thoughtful policy approaches prioritizing just transition principles.

The Role of Natural Gas in Energy Transition

Some energy analysts argue that natural gas plays a necessary role during the transition toward renewable energy dominance. This “bridge fuel” concept suggests that natural gas can replace coal while renewable capacity expands, providing reliable baseload power during the transition period. This argument contains surface logic but increasingly fails scrutiny when examining climate timelines and technological capabilities.

The International Energy Agency and other authoritative sources indicate that achieving climate stability requires rapid renewable energy deployment over the next 1-2 decades. Investing in natural gas infrastructure with 30-40 year operational lifespans conflicts directly with this timeline. New natural gas plants built today will likely operate through 2050-2060, locking in fossil fuel emissions during the critical period when climate action must accelerate dramatically. This incompatibility with climate requirements makes the bridge fuel argument increasingly untenable.

Battery storage technology, grid management improvements, and renewable energy expansion have progressed to the point where natural gas is no longer necessary for grid reliability in most developed regions. Countries including Denmark, Uruguay, and Costa Rica have demonstrated that high renewable energy penetration is technically feasible and economically viable without substantial natural gas dependence. These examples suggest that the bridge fuel narrative reflects political interests rather than technical necessity.

Natural gas may continue playing minor roles in specific applications where alternatives remain limited—certain industrial processes, high-temperature heating, and backup generation for grid stability. However, expanding natural gas infrastructure for these niche applications cannot be justified. Instead, research and investment should focus on developing alternatives including green hydrogen, advanced electrification, and industrial process innovations that eliminate fossil fuel dependence entirely.

Achieving reduced environmental footprints requires transitioning away from all fossil fuels, including natural gas. While natural gas produces fewer emissions than coal during combustion, its complete lifecycle impacts, methane leakage risks, extraction consequences, and infrastructure lock-in effects make it fundamentally unsustainable. Genuine progress toward climate stability demands accelerated renewable energy deployment and systematic phase-out of fossil fuel dependence.

FAQ

Is natural gas considered a renewable energy source?

No, natural gas is a fossil fuel formed over millions of years from organic matter. It is non-renewable because it cannot be replenished on human timescales. Once extracted and burned, the resource is permanently depleted. This fundamental characteristic distinguishes natural gas from truly renewable sources like solar, wind, and hydroelectric power that regenerate continuously.

How much methane leakage occurs in natural gas systems?

Methane leakage rates typically range from 1-8% of total production, varying significantly based on infrastructure age, maintenance standards, and extraction methods. Some studies of unconventional shale gas operations have documented leakage rates exceeding 5%. Even at the lower end of estimates, methane leakage substantially reduces natural gas’s climate benefits compared to coal, particularly when considering methane’s high global warming potential.

Can natural gas be considered a bridge fuel toward renewable energy?

The bridge fuel concept faces increasing criticism from climate scientists. While natural gas produces fewer emissions than coal during combustion, new natural gas infrastructure would operate for 30-40 years, locking in fossil fuel dependence through 2050-2060. Climate targets require rapid renewable deployment within the next 1-2 decades, making long-term natural gas investments incompatible with climate goals. Additionally, renewable energy and storage technology have advanced to provide reliable alternatives without natural gas.

What are the main environmental impacts of natural gas extraction?

Natural gas extraction impacts include land disturbance, groundwater contamination risks (particularly with hydraulic fracturing), freshwater consumption, chemical waste generation, induced seismicity, methane leakage, and ecosystem disruption. Unconventional extraction methods like fracking present greater environmental risks than conventional drilling. Arctic natural gas development creates additional concerns regarding fragile ecosystem impacts and climate feedback effects from ice melt acceleration.

How does natural gas compare to renewable energy for sustainability?

Renewable energy sources including solar, wind, and hydroelectric power produce electricity with approximately one-quarter to one-tenth the lifecycle emissions of natural gas when accounting for methane leakage. Renewables avoid extraction impacts, fuel supply chains, and combustion emissions entirely. Battery storage technology and grid management improvements have advanced sufficiently to provide renewable energy reliability without natural gas backup in most developed regions, making renewables superior from both climate and sustainability perspectives.

What percentage of global energy comes from natural gas?

Natural gas currently supplies approximately 20-22% of global primary energy, making it the third-largest energy source after oil and coal. Despite climate concerns, natural gas consumption has continued growing in recent decades, driven by industrial applications, electricity generation, and heating. However, achieving climate targets requires declining natural gas use, replaced by renewable energy expansion and improved energy efficiency rather than substitution with alternative fossil fuels.