Natural Gas: Renewable or Not? Expert Insight

The question of whether natural gas is renewable has become increasingly important as societies worldwide grapple with climate change and energy transition. Natural gas occupies a complex position in our energy landscape—often promoted as a transitional fuel toward cleaner energy, yet fundamentally limited by its fossil fuel origins. Understanding this distinction requires examining the source, formation, and sustainability implications of natural gas as an energy resource.

For decades, natural gas has been positioned as the “cleaner” alternative to coal and oil. Its lower carbon emissions per unit of energy make it attractive to policymakers seeking immediate reductions in greenhouse gases. However, this narrative masks a critical truth: natural gas is nonrenewable, not renewable. Like oil and coal, natural gas is a finite fossil fuel formed from organic matter over millions of years—a timeframe far exceeding human civilization. While some emerging technologies explore renewable alternatives like biomethane, the conventional natural gas supply depends on depleting geological reserves that cannot be replenished within meaningful human timescales.

What Is Natural Gas and How Is It Formed?

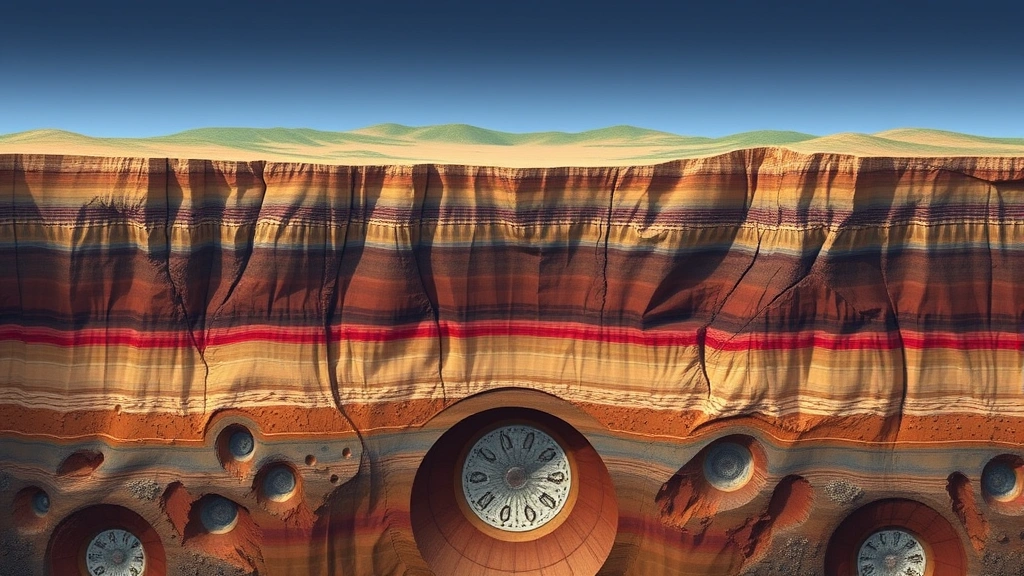

Natural gas is a fossil fuel composed primarily of methane (CH₄), along with smaller quantities of ethane, propane, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide. It forms deep beneath the Earth’s surface through the decomposition of organic matter—dead plants, animals, and microorganisms—subjected to intense heat and pressure over millions of years. This geological process, occurring in sedimentary rock layers, transforms ancient biological material into a gaseous hydrocarbon that accumulates in porous rock formations.

The formation process is extraordinarily slow. It typically requires 50 to 200 million years for sufficient organic matter to break down and convert into commercially viable natural gas reserves. This timescale is the fundamental reason natural gas cannot be considered renewable—humans cannot meaningfully replenish what takes geological epochs to create. Current global consumption rates far exceed any natural regeneration, making natural gas extraction fundamentally unsustainable from a long-term perspective.

Natural gas is extracted through conventional drilling in onshore and offshore fields, or through unconventional methods like hydraulic fracturing (fracking) in shale formations. Once extracted, it’s processed, transported via pipelines or liquefied for shipping, and distributed to residential, commercial, and industrial consumers. This extensive infrastructure has made natural gas deeply embedded in modern energy systems across heating, electricity generation, and industrial processes.

Renewable vs. Nonrenewable Energy: Definitions Matter

The distinction between renewable and nonrenewable energy is scientifically straightforward, yet often misunderstood in public discourse. Renewable energy sources are those that naturally replenish on human timescales—typically within years or decades. Solar, wind, hydroelectric, geothermal, and biomass energy fall into this category. They either derive from continuous natural processes (sunlight, wind patterns, water cycles) or can be grown and harvested sustainably within reasonable timeframes.

Nonrenewable energy sources, conversely, deplete finite reserves that took millions of years to form. Coal, oil, and natural gas are the primary nonrenewable energy sources. Once extracted and burned, they cannot be replaced within any meaningful human timeframe. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency explicitly classifies natural gas as a nonrenewable fossil fuel, establishing clear regulatory and scientific consensus on this classification.

Understanding principles of sustainability requires recognizing this fundamental difference. A truly sustainable energy system must transition away from nonrenewable resources toward renewable alternatives. While natural gas may play a temporary bridging role, it cannot be part of a long-term sustainable energy strategy precisely because reserves are finite and depletion is inevitable.

Why Natural Gas Is Classified as Nonrenewable

Natural gas receives its nonrenewable classification for several interconnected reasons rooted in geology, thermodynamics, and resource availability:

- Geological Formation Timescale: The millions of years required for natural gas formation vastly exceeds human lifespans and even civilizational timescales. We cannot accelerate this process through any known technology.

- Finite Reserves: Global natural gas reserves, while substantial, are quantifiable and diminishing. The U.S. Geological Survey and International Energy Agency track these reserves, confirming they represent finite resources approaching depletion within 50-70 years at current consumption rates.

- No Natural Regeneration: Unlike forests that regrow or wind that continuously blows, natural gas deposits do not regenerate. Once extracted, they are gone permanently.

- Energy Return on Investment: Extracting natural gas requires significant energy investment. The energy required to drill, process, and transport natural gas leaves less net energy benefit than renewable sources like solar and wind.

- Irreversible Consumption: Burning natural gas converts it into carbon dioxide and water vapor—a chemical transformation that cannot be reversed. The resource is consumed, not recycled.

These factors combine to create an unambiguous scientific reality: natural gas is nonrenewable. However, the energy industry and some policymakers have promoted natural gas as a “bridge fuel” or “transition fuel,” which has created confusion about its renewable status. This marketing framing emphasizes natural gas’s lower carbon emissions compared to coal, while obscuring its nonrenewable nature and long-term sustainability limitations.

The Methane Emissions Problem

Beyond the fundamental issue of resource depletion, natural gas presents another critical sustainability challenge: methane emissions throughout its supply chain. Methane is 28-34 times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping atmospheric heat over a 100-year period, making even small leakage rates highly significant.

Methane escapes at multiple points: during extraction at the wellhead, in processing facilities, through pipeline transport, and at distribution points. Studies by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and independent researchers have documented that actual methane leakage rates often exceed industry estimates, sometimes reaching 3-4% of production. When methane leakage is factored into lifecycle carbon accounting, natural gas’s climate advantage over coal diminishes substantially.

For methane from natural gas to be preferable to coal from a climate perspective, leakage must remain below approximately 3%. Many studies suggest actual leakage exceeds this threshold, particularly when accounting for fugitive emissions difficult to measure. This reality undermines the primary argument for natural gas as a transition fuel—if it leaks methane at high rates, its climate benefit becomes marginal or nonexistent.

The methane problem is exacerbated by unconventional extraction methods. Hydraulic fracturing, used to extract shale gas, involves injecting pressurized fluids deep underground to fracture rock formations. This process increases methane leakage risks and raises additional environmental concerns regarding groundwater contamination and seismic activity.

Natural Gas as a Transition Fuel

Despite being nonrenewable, natural gas is frequently discussed as a transition fuel in energy transition frameworks. This concept acknowledges that global energy systems cannot shift instantaneously from fossil fuels to renewables. Natural gas, producing roughly 50% fewer emissions than coal per unit of electricity, offers a lower-emission alternative during this transition period.

The transition fuel argument contains logical merit from a practical standpoint. Existing infrastructure—power plants, heating systems, industrial equipment—cannot be replaced overnight. Natural gas can utilize some existing infrastructure while new renewable capacity is developed. For regions heavily dependent on coal, transitioning to natural gas represents immediate emissions reductions.

However, this framework contains dangerous assumptions. First, it assumes a definite timeline for transition to renewables—a timeline that continues slipping as fossil fuel infrastructure receives continued investment. Second, it risks locking in natural gas infrastructure for decades, creating what energy analysts call “stranded assets” and “carbon lock-in.” Third, it assumes natural gas will genuinely be temporary, when historical patterns show fossil fuel transitions take 50+ years, during which nonrenewable resources deplete and climate impacts accelerate.

For sustainable energy solutions, the transition fuel model should be viewed skeptically. Rather than extending natural gas infrastructure, accelerated renewable deployment offers faster emissions reductions and genuine long-term sustainability. The International Energy Agency’s net-zero scenarios increasingly minimize natural gas’s role, prioritizing direct renewable electrification instead.

Renewable Gas Alternatives and Biomethane

An important distinction exists between conventional natural gas and renewable gas alternatives. Biomethane (also called biogas) and synthetic methane represent genuinely renewable or low-carbon alternatives to fossil natural gas, though they currently constitute a tiny fraction of global gas supply.

Biomethane is produced through anaerobic digestion of organic waste—agricultural residues, food processing waste, wastewater treatment sludge, or dedicated energy crops. Microorganisms break down organic material in oxygen-free environments, producing methane-rich biogas that can be upgraded to pipeline quality. Since biomethane comes from recently living organic matter rather than ancient fossilized deposits, it qualifies as renewable. Its carbon cycle is relatively neutral: the carbon released when biomethane is burned roughly equals the carbon absorbed during the growth of source materials.

Synthetic methane produced through power-to-gas processes represents another emerging alternative. Renewable electricity powers electrolysis to produce hydrogen, which is then combined with carbon dioxide (potentially captured from atmosphere or industrial sources) to create synthetic methane. This pathway could theoretically be completely renewable and carbon-neutral if powered entirely by renewable electricity and utilizing captured carbon.

However, both alternatives face significant scalability challenges. Biomethane production is limited by available organic waste and sustainable biomass resources. Synthetic methane requires substantial energy inputs and remains expensive compared to fossil natural gas. Current global biomethane production represents less than 1% of natural gas supply, with limited prospects for dramatic expansion within coming decades.

These renewable gas alternatives are genuinely important for specific applications—industrial heat requiring very high temperatures, long-distance transportation, seasonal energy storage—where electrification proves technically difficult. However, they cannot replace the massive fossil natural gas infrastructure currently in place. Their role should be strategic and limited, not a justification for expanding conventional natural gas infrastructure.

The Future of Natural Gas in a Sustainable World

As climate science increasingly demands rapid emissions reductions, natural gas’s role in sustainable energy futures contracts. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports emphasize that limiting warming to 1.5°C requires dramatic emissions reductions this decade, with fossil fuel use declining by roughly 45% by 2030. This timeline leaves minimal room for extended natural gas expansion.

Leading climate scenarios increasingly show natural gas declining from current levels rather than growing. This represents a fundamental shift from 20th-century energy transition models that assumed natural gas would play a major bridging role. Instead, the most cost-effective pathway to decarbonization involves accelerating renewable electricity deployment and direct electrification of heating, transportation, and industrial processes.

For residential consumers, this means transitioning away from natural gas heating toward energy-efficient heat pumps and renewable heating solutions. For transportation, advantages of electric vehicles over fossil fuel alternatives continue improving as electricity grids decarbonize. For industry, direct renewable electricity and renewable hydrogen increasingly displace natural gas in viable applications.

Investment decisions made today regarding natural gas infrastructure will determine energy systems for decades. New natural gas pipelines and liquefied natural gas terminals represent 40-50 year commitments, locking in emissions and resource depletion far into a period when climate imperatives demand near-zero fossil fuel use. From a sustainability perspective, such infrastructure investments are increasingly difficult to justify.

The International Energy Agency and other authoritative bodies recognize that genuine energy sustainability requires moving beyond all fossil fuels, including natural gas. While near-term natural gas use may continue in certain contexts, building long-term energy systems around nonrenewable resources contradicts fundamental sustainability principles.

FAQ

Is natural gas renewable?

No. Natural gas is nonrenewable. It is a fossil fuel formed from organic matter over millions of years. Once extracted and burned, it cannot be replaced on human timescales. While renewable alternatives like biomethane exist, conventional natural gas extracted from geological reserves is definitively nonrenewable.

Why do people call natural gas a “transition fuel”?

Natural gas produces approximately 50% fewer emissions than coal when burned for electricity generation. This led energy analysts and policymakers to propose it as a temporary bridge fuel during the transition from coal to renewable energy. However, this framework is increasingly criticized because it risks locking in fossil fuel infrastructure and delays the rapid transition to genuine renewables that climate science demands.

What is biomethane and how does it differ from natural gas?

Biomethane is a renewable gas produced from organic waste through anaerobic digestion. Unlike fossil natural gas, biomethane comes from recently living organic matter and can be continuously produced. However, current biomethane production represents less than 1% of global gas supply and faces scalability limitations.

How long will natural gas reserves last?

At current consumption rates, global natural gas reserves are estimated to last approximately 50-70 years. However, this timeline assumes stable consumption. Increased extraction to replace declining coal and oil would accelerate depletion, while efficiency improvements and renewable energy adoption would extend reserves. Regardless, the finite nature of these reserves makes natural gas unsustainable long-term.

What are the methane emissions problems with natural gas?

Methane leaks throughout the natural gas supply chain—from extraction, processing, transport, and distribution. Methane is 28-34 times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping heat. When leakage rates exceed approximately 3%, natural gas offers minimal climate advantage over coal. Studies suggest actual leakage often exceeds this threshold, undermining natural gas’s climate credentials.

What should replace natural gas in sustainable energy systems?

Renewable electricity, heat pumps, renewable hydrogen, and biomethane (for specific applications) should replace natural gas. Direct electrification powered by renewable sources offers faster emissions reductions and genuine long-term sustainability compared to transitioning to another fossil fuel.