Are Old Gas Pumps Eco-Friendly? Expert Analysis

The infrastructure that has fueled transportation for over a century—traditional gas pumps—represents far more than a convenient refueling mechanism. These ubiquitous machines embody the environmental legacy of the fossil fuel era, raising critical questions about their ecological impact and sustainability. As the world transitions toward cleaner energy alternatives, understanding the environmental footprint of old gas pumps becomes essential for policymakers, business owners, and environmentally conscious consumers.

This comprehensive analysis examines the ecological implications of aging fuel distribution infrastructure, from volatile organic compound emissions to groundwater contamination risks. We’ll explore how these systems compare to modern alternatives and what their continued operation means for our climate and environmental health. By dissecting the science behind gas pump emissions and infrastructure decay, we can better understand why the transition to sustainable energy solutions is not merely an option but an environmental imperative.

How Old Gas Pumps Impact Air Quality

Gasoline vapors released during refueling represent one of the most direct environmental impacts of old gas pump systems. When vehicles pull up to traditional fuel dispensers, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) escape into the atmosphere through a process called evaporation. These emissions occur at multiple points: during the transfer of fuel from underground storage tanks to the pump, through the nozzle during dispensing, and from vehicle fuel tanks themselves.

The environmental significance of these emissions extends beyond simple air quality degradation. VOCs interact with nitrogen oxides in the presence of sunlight to form ground-level ozone, a major air pollutant linked to respiratory diseases, cardiovascular problems, and reduced lung function. The Environmental Protection Agency has documented that ozone pollution costs billions in healthcare expenses annually and contributes to thousands of premature deaths.

Older gas pumps, particularly those installed before the 1990s, often lack vapor recovery systems—technology designed to capture and recycle fuel vapors back into underground storage tanks. Without these systems, every gallon of gasoline dispensed releases approximately 5-10 grams of volatile compounds directly into the breathing air of refueling station attendants and nearby communities. Modern pumps equipped with Stage II vapor recovery systems can reduce these emissions by up to 95%, highlighting the substantial environmental advantage of upgrading aging infrastructure.

The cumulative effect across millions of gas stations worldwide is staggering. A single outdated pump operating for 20 years without vapor recovery can release hundreds of tons of VOCs into the atmosphere. When multiplied across the estimated 150,000+ gas stations globally, the aggregate impact on air quality and climate becomes a significant environmental concern that demands urgent attention.

Groundwater Contamination and Soil Degradation

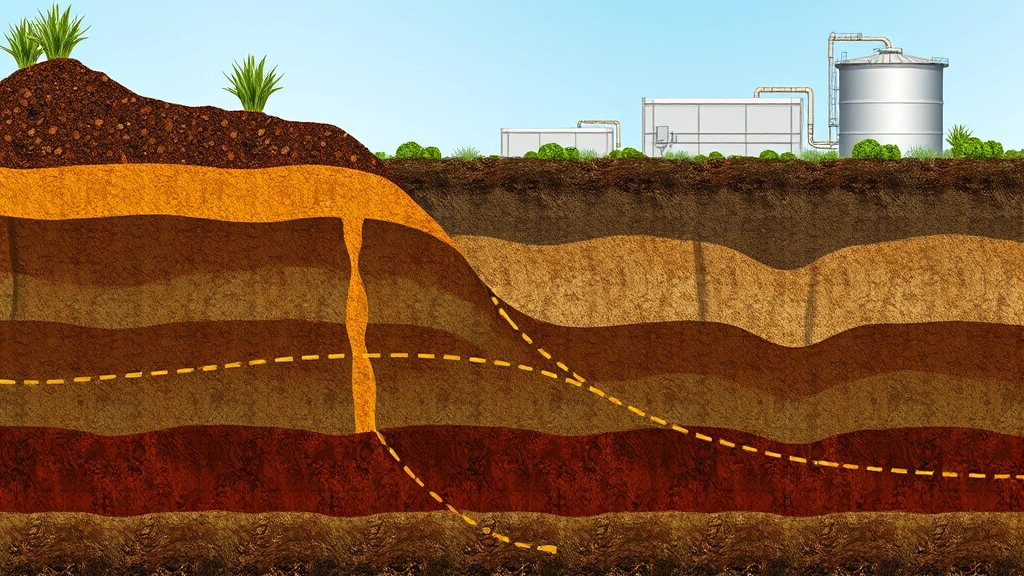

Beyond atmospheric emissions, old gas pumps pose substantial risks to water resources and soil ecosystems. Underground storage tanks (USTs) that supply traditional gas pumps frequently leak, contaminating groundwater supplies that millions depend upon for drinking water, irrigation, and industrial processes. The American Petroleum Institute estimates that over 500,000 leaking underground storage tanks exist across the United States alone, many associated with aging fuel distribution infrastructure.

Benzene, a carcinogenic compound found in gasoline, can migrate through soil layers and reach aquifers within months or years, depending on geological conditions. Once groundwater contamination occurs, remediation efforts can span decades and cost millions of dollars. Communities with contaminated wells often face restricted water access, forced reliance on bottled water, and increased cancer risks among residents—a tragic consequence of aging fuel infrastructure.

The United States Geological Survey emphasizes that groundwater remediation from petroleum contamination represents one of the most persistent environmental challenges facing municipalities. The permanence of these contamination zones means that decisions made today about maintaining or replacing old gas pump infrastructure will impact water quality for generations to come.

Soil degradation extends beyond chemical contamination. The heavy equipment required to install and maintain old pump systems compacts soil, reducing its capacity to support vegetation and filter water naturally. This degradation diminishes soil’s ability to sequester carbon—a critical function in mitigating climate change. Replacing old gas pump infrastructure with sustainable alternatives like electric vehicle charging networks would eliminate these soil and water contamination risks entirely.

Emissions During Fuel Transfer

The mechanical process of transferring gasoline from delivery trucks to underground storage tanks and subsequently to vehicle fuel tanks generates substantial emissions at each stage. Old gas pump systems often lack sophisticated monitoring and control mechanisms that modern equipment provides, resulting in unnecessary spillage, overfilling, and vapor escape.

During the delivery phase, fuel truck operators must connect hoses to tank openings on older systems that may have degraded seals or improper ventilation design. These connections frequently allow vapors to escape before the fuel even reaches the storage tank. Once in underground storage, aging tanks may have corroded internal surfaces or compromised structural integrity, creating pathways for fuel and vapors to escape into surrounding soil and groundwater.

The final transfer stage—from storage tank to vehicle—represents the most visible source of emissions. Consumers often notice fuel odors while refueling, which reflects the escape of volatile compounds. This sensory experience, while seemingly minor, indicates substantial environmental release. Studies conducted by environmental research organizations have documented that a single refueling event at a pump without vapor recovery systems releases the equivalent VOC content of driving a vehicle for several miles.

Temperature fluctuations affect emission rates significantly. During warm seasons, gasoline volatility increases, causing greater vapor release during fuel transfer operations. Older pump systems lack temperature-control mechanisms that modern infrastructure incorporates, meaning summer months see dramatically elevated emissions at aging gas stations. This seasonal variation underscores how outdated technology becomes increasingly problematic as climate patterns shift toward more extreme temperature variations.

Infrastructure Age and Environmental Risks

The average lifespan of a gas pump is approximately 15-20 years, yet many pumps operating today exceed this threshold significantly. Equipment degradation accelerates environmental damage through multiple pathways. Corroded metal components allow fuel leakage, worn seals permit vapor escape, and degraded electrical systems may malfunction, preventing proper safety protocols from engaging.

Regulatory agencies increasingly recognize that aging infrastructure represents an unacceptable environmental liability. The EPA’s Underground Storage Tank program mandates regular inspections and maintenance of systems over 10 years old, yet compliance remains inconsistent. Many facility owners defer costly upgrades or replacements, allowing environmental degradation to continue.

The economic calculus often favors short-term cost reduction over environmental responsibility. Replacing a single gas pump costs $3,000-$5,000, while replacing an entire underground storage tank system can exceed $100,000. These substantial expenses create perverse incentives to maintain aging infrastructure longer than environmentally prudent. However, the hidden costs of contamination cleanup, health impacts, and regulatory penalties often exceed upgrade costs when calculated comprehensively.

Climate change amplifies risks associated with old gas pump infrastructure. Extreme weather events damage aging systems more severely than modern equipment. Flooding can rupture old storage tanks, releasing thousands of gallons of gasoline into the environment. Hurricanes and severe storms disproportionately impact facilities with aging infrastructure, as modern systems incorporate resilience features that older equipment lacks.

Comparing Old and Modern Pump Technology

Contemporary gas pump technology incorporates environmental safeguards absent from older systems. Modern pumps feature Stage II vapor recovery systems that capture fuel vapors during dispensing and route them back into storage tanks, preventing atmospheric release. These systems reduce VOC emissions by 95% compared to uncontrolled systems, representing a transformative improvement in reducing air pollution from refueling operations.

Advanced monitoring systems on modern pumps detect leaks immediately, alerting operators to maintenance needs before significant environmental damage occurs. Sensors monitor pressure differentials, temperature variations, and flow rates, identifying anomalies that indicate equipment malfunction or deterioration. This proactive approach prevents the gradual environmental degradation characteristic of aging systems that lack such monitoring capabilities.

Modern underground storage tanks employ double-wall construction with interstitial monitoring systems that detect leaks in the outer tank wall before fuel reaches the environment. These design features represent a fundamental advancement in preventing groundwater contamination. Older single-wall tanks lack this redundancy, meaning any structural compromise allows immediate environmental contamination.

The definition of sustainability encompasses meeting present needs without compromising future generations’ ability to meet theirs. By this standard, maintaining old gas pump infrastructure fails the sustainability test, as it perpetuates environmental degradation and defers remediation costs to future generations. Modern pump technology, while still dependent on fossil fuels, substantially reduces the environmental damage associated with fuel distribution infrastructure.

However, the most sustainable approach involves transitioning away from gasoline-dependent infrastructure entirely. Sustainable energy solutions centered on electric vehicle charging networks eliminate fuel transfer emissions, groundwater contamination risks, and air pollution from refueling operations. This transition represents the ultimate environmental upgrade from aging gas pump systems.

Regulatory Standards and Compliance Issues

Environmental regulations governing gas pump infrastructure have evolved substantially over the past three decades, reflecting growing awareness of environmental and health impacts. The Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 mandated vapor recovery systems for new pumps, yet millions of older systems remain exempt from these requirements. This regulatory grandfather clause allows environmentally damaging equipment to continue operating indefinitely.

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) established standards for underground storage tank management, including leak detection, corrosion protection, and spill containment. However, compliance remains inconsistent, and enforcement resources are often insufficient to ensure widespread adherence. Facility owners in jurisdictions with limited environmental agency capacity face minimal pressure to upgrade aging systems.

State-level regulations vary dramatically, creating a patchwork of environmental standards. Some states mandate comprehensive inspections and upgrades of aging systems, while others impose minimal requirements. This regulatory fragmentation means that the environmental impact of old gas pump infrastructure depends partly on geographic location—a situation that contradicts the principle that environmental protection should be uniform regardless of jurisdiction.

International standards through organizations like the International Organization for Standardization establish best practices for fuel storage and distribution, yet adoption remains voluntary in many regions. Countries with stringent environmental regulations have successfully phased out aging gas pump infrastructure, demonstrating that regulatory frameworks effectively drive environmental improvements when implemented comprehensively.

The Case for Transitioning to Electric Infrastructure

The most compelling argument against maintaining old gas pumps involves recognizing that gasoline-dependent transportation itself represents an unsustainable energy paradigm. Rather than investing resources in modernizing aging fuel distribution infrastructure, the rational environmental response involves accelerating the transition to electric vehicle charging networks and green technology innovations.

Electric vehicle charging infrastructure eliminates the entire category of environmental problems associated with gasoline fuel distribution. No VOC emissions occur during charging, no groundwater contamination risks exist, and no air pollution results from the refueling process itself. While electricity generation may still depend partly on fossil fuels in many regions, the efficiency advantage of electric motors means that even fossil-fuel-generated electricity produces fewer emissions per mile traveled than gasoline combustion.

The economic transition from gas pump infrastructure to electric charging networks requires substantial investment, but this capital reallocation represents necessary infrastructure modernization rather than an additional expense. Money currently spent maintaining aging gas pump systems can be redirected toward charging network installation. Over the long term, electric charging infrastructure requires less maintenance and poses fewer environmental liabilities than fuel distribution systems.

Behavioral changes accompanying this infrastructure transition amplify environmental benefits. Charging at home or work locations reduces unnecessary vehicle trips to refueling stations, decreasing overall transportation emissions. Fleet electrification in commercial and public sectors demonstrates that electric alternatives are technically feasible and economically viable at scale. Cities and regions implementing comprehensive electric vehicle transition plans show that old gas pump infrastructure becomes rapidly obsolete as charging networks expand.

The SustainWise Hub Blog regularly explores the implications of infrastructure transitions toward sustainable energy systems. Understanding how energy consumption patterns shift with technological change provides context for evaluating whether maintaining aging gas pump infrastructure represents prudent environmental stewardship or delayed recognition of necessary systemic transformation.

Progressive cities worldwide have begun restricting new gas pump installations and establishing timelines for phasing out gasoline-dependent transportation. California, several Scandinavian countries, and the United Kingdom have implemented ambitious policies targeting the end of fossil fuel vehicle sales within 10-20 years. These regulatory frameworks effectively render old gas pump infrastructure obsolete, accelerating the transition to sustainable alternatives.

FAQ

Do old gas pumps have vapor recovery systems?

Many older gas pumps lack Stage II vapor recovery systems, particularly those installed before the 1990s. These systems capture fuel vapors during dispensing and return them to storage tanks, reducing atmospheric emissions by up to 95%. Older pumps without this technology release substantially more volatile organic compounds into the atmosphere, contributing to air pollution and ground-level ozone formation.

What environmental damage can leaking underground storage tanks cause?

Leaking underground storage tanks contaminate groundwater with benzene and other carcinogenic compounds, affecting drinking water supplies and requiring expensive remediation. Contamination can persist for decades, rendering aquifers unusable and forcing communities to rely on alternative water sources. Soil degradation also occurs around leaking tanks, reducing the land’s ability to support vegetation and sequester carbon.

How do modern gas pumps compare environmentally to old ones?

Modern gas pumps incorporate vapor recovery systems, advanced leak detection, and monitoring technology that substantially reduce environmental impacts. They feature double-wall storage tanks with interstitial monitoring, temperature controls, and automated safety systems absent from older equipment. However, even modern gas pumps remain environmentally problematic compared to electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

Are old gas pumps being phased out?

Regulatory frameworks in progressive jurisdictions increasingly restrict new gas pump installations and establish timelines for phasing out gasoline-dependent transportation. California and Scandinavian countries have implemented policies targeting the end of fossil fuel vehicle sales, effectively rendering old gas pump infrastructure obsolete. However, many regions lack such policies, allowing aging systems to continue operating.

What is the most sustainable alternative to gas pumps?

Electric vehicle charging networks represent the most sustainable alternative, eliminating fuel transfer emissions, groundwater contamination risks, and air pollution from refueling operations. While electricity generation may still depend partly on fossil fuels, electric motors’ efficiency advantage produces substantially lower emissions per mile traveled. Transitioning infrastructure investment from gas pumps to charging networks accelerates sustainable transportation adoption.

How much do old gas pumps contribute to air pollution?

A single outdated pump without vapor recovery releases 5-10 grams of volatile organic compounds per gallon dispensed. Across millions of gas stations globally, this accumulates to hundreds of millions of tons of VOCs annually, contributing significantly to ground-level ozone formation, respiratory diseases, and premature mortality. The environmental impact is substantial and measurable at both local and global scales.